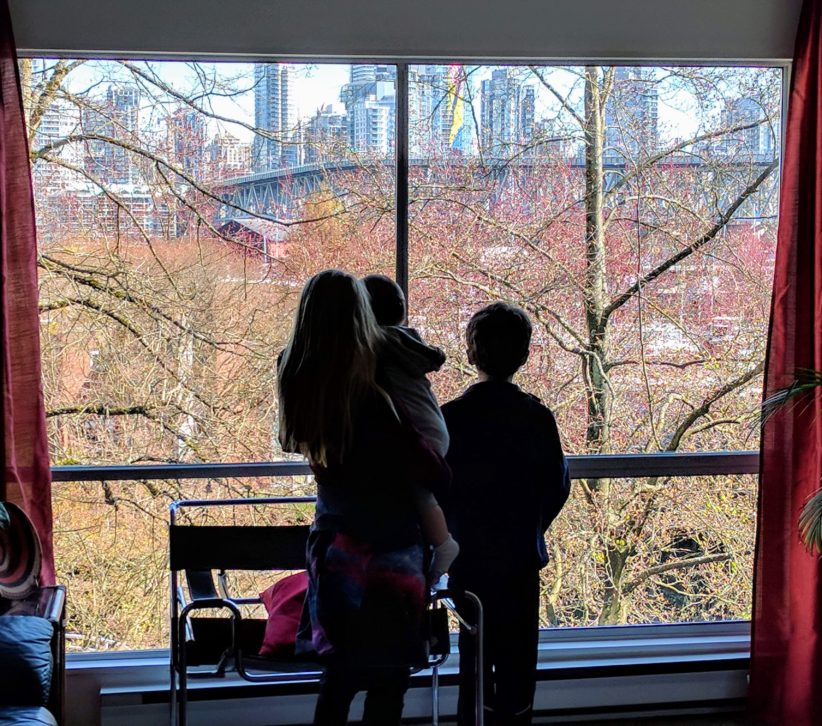

This is the second installment in a two-part guest post (you can find the first part here). The author is my friend Dr. Matt Poyner, a Canadian emergency physician who sold everything, quit his job, and is currently backpacking the world with his wife and four young sons.

Over several months Matt and I have discussed burnout, purpose, family responsibilities and religion - he's become that kind of friend despite never having met face-to-face. Making these connections is a big part of the reason I blog.

After I wrote a post on anger, Matt shared that one of his professional interests had been handling a specific type of anger all physicians must learn to navigate - patient complaints. In fact, he had lectured at conferences as an expert on the subject. I feel fortunate that he's agreed to share his expertise here. Back to you, Matt.

A PAINfully simple approach

You’re probably already getting the idea of what a good response would look like. Our medical world is filled with acronyms, so I came up with one that I hope is easy to remember because it reflects how I think all of us feel about patient complaints: they’re a PAIN (i.e. in the ass).

So let’s go through them one by one.

P is for PREPARE

- You wouldn’t treat any other patient without reviewing the case so don’t treat complaints any differently. Do your homework. Review both the chart and the patient’s concerns in detail then sleep on it. Let your limbic system (remember neurology? - that’s the angry, defensive part) simmer down for a while before starting your response.

- But don’t delay the response for more than a week - their anger may fester and you risk escalation

A is for APOLOGIZE

- Remember: an apology is not the same as accepting responsibility. It shows that you value your patients more than your pride.

- You can apologize for the patient’s suffering, without it being your fault. You can apologize that their expectations were not met even if those expectations were unreasonable

- this is NOT admitting responsibility, rather showing empathy for the patient’s experience.

- But if a mistake was made, it can be even more important to apologize. (If there is risk of a lawsuit, it is prudent to seek legal advice, but many hospital level complaints are made by patients who are seeking resolution outside the legal system - more on this in a minute)

I is for INFORM

- Many complaints are made because patients don’t understand why things happened the way they did. This is your chance to explain, in layman’s terms,what you did and why you did it

- I also use the opportunity to say explicitly that I care about the quality of my work and about their case in particular. I think it helps to put that in writing.

- Lastly, I make sure I answer any specific concerns

N is for NEXT STEPS

- Patients want to know that their complaint is not falling on deaf ears. We need to show a willingness to improve - either ourselves, or the system we work in - or both. God knows there is room for improvement

- If there was something you could have done better, admit it

- Commit to improving in some way: read up on the condition, use the case to make a positive change in the system, present the case at rounds so that others can learn (with the patient’s permission, of course)

So, respond to the PAIN. Just remember, THEIR goal is to 1) understand what happened and 2) make sure the same thing doesn’t happen to someone else.

OUR goal is to 1) resolve the issue with as little pain as possible and 2) use the feedback to become better physicians.

The benefits of conflict resolution

It’s important to realize there is common ground - we both want a resolution. As difficult as this process may seem, there are huge benefits to engaging in the process.

The evidence is clear - when a physician has made an error, a sincere apology coupled with an explanation leads to fewer lawsuits. In fact, there was a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine showing that in one jurisdiction, malpractice lawsuits were cut in half after doctors were legally allowed to openly disclose their mistakes to patients.

Other studies of lawsuits already launched show that a large portion of the plaintiffs would not have sued if they had received - you guessed it - an apology and an explanation.

Complaints are an opportunity

“It takes both sides to build a bridge” - Fredrik Nael

None of us want to get sued. And, believe it or not, most patients don’t want to sue us. But in a large number of cases, they sue because it is seen as the only means of resolution.

So, if it’s possible to view complaints in a positive light, it’s this: a hospital level complaint is an opportunity to provide a resolution before the issue escalates.

Unfortunately, due to the unpredictable and high-stress nature of medicine, complaints are an inevitable part of the job. Just like difficult airways (for ER docs), we just have to expect that they are coming - but we don’t have to feel unprepared.

Summary - the PAIN approach

PREPARE - read the chart and the complaint carefully; prepare yourself emotionally

APOLOGIZE - the most difficult and the most important thing to do; show empathy

INFORM - explain what you did and why you did it; answer their specific concerns

NEXT STEPS - what will you do to make sure it doesn’t happen again?

About the author: Matt is an ER doctor who has worked for thirteen years in Ontario, Canada. After a particularly gruesome public relations disaster involving his ER a few years ago, he became a local expert on how to better manage patient relations. He has given his talk as a plenary at Canada’s largest ER conference (North York Emergency Medicine Update) and at several smaller venues. Since reaching FI about a year ago, Matt is now traveling around the world with his wife and four boys while blogging at www.big-family-small-world.com. He can be reached at bfsw2018@gmail.com.