I have read that a raccoon will wash a perfectly clean food item in filthy water before consuming it as a matter of genetically-based behavior. The inclination to rinse food prior to eating it must have historically served as an evolutionary advantage, even if in some circumstances it may harm the raccoon.

In a similar vein, I hail from a pathological lineage of collectors. My maternal grandfather collected and sorted stamps, which he sorted with care into enormous volumes made for that express purpose by societies of like-minded philatelists.

My father's collections include carved ironwood sculptures from rural Mexico; soapstone etchings from South Africa; small chrome timepieces that can be found in any Chinatown tourist shop; paintings of rural landscapes from his native Cuba; and colorful solar-powered yard lights that recreate Disney's Main Street Electrical Parade nightly.

I have collected old film cameras and 8mm film videocameras from back when home movies did not have sound; books by the beat writer Richard Brautigan; Ethiopian ceremonial crosses; and most recently, books on the history of medicine. The latter collection at one point approached a hundred books, which a sincere desire to live leaner has led me to pare down to the 15 volumes I found most meaningful and important.

The jewel of my remaining collection is a book called Occupational Marks by the dermatologist Franchesco Ronchese, MD. Published in 1948, it is the sort of dusty, leatherbound volume that invites a rich glimpse of a bygone era.

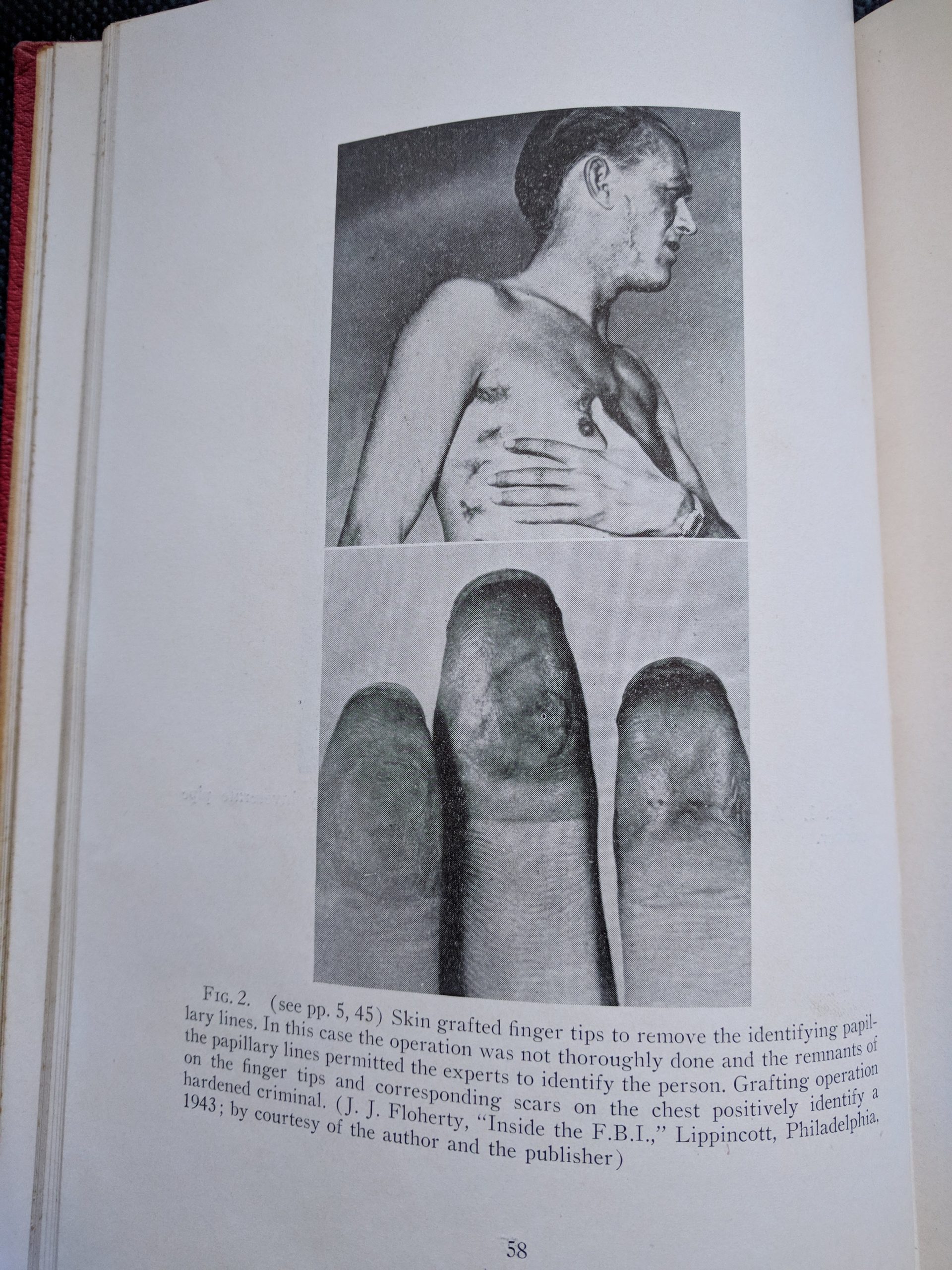

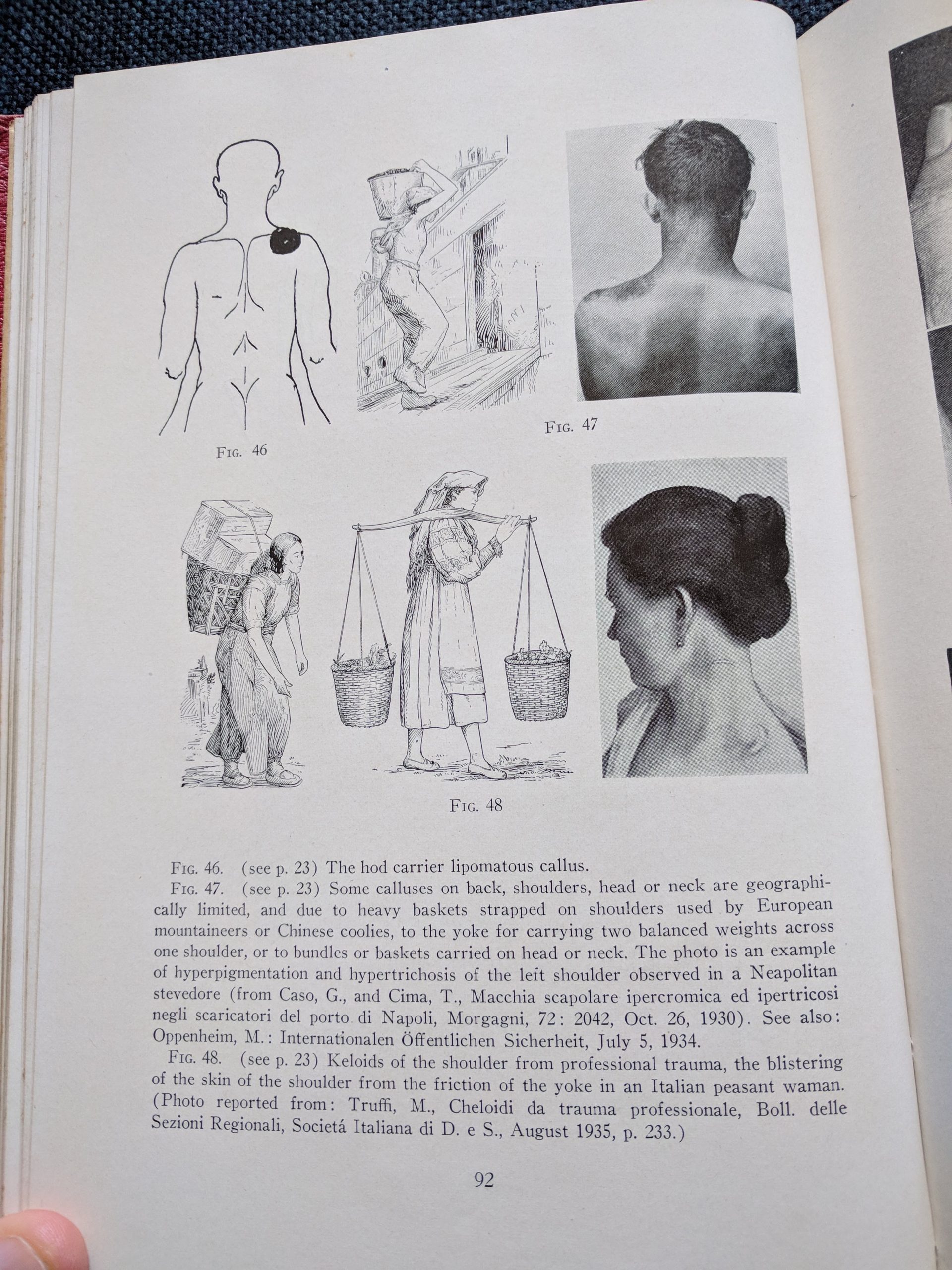

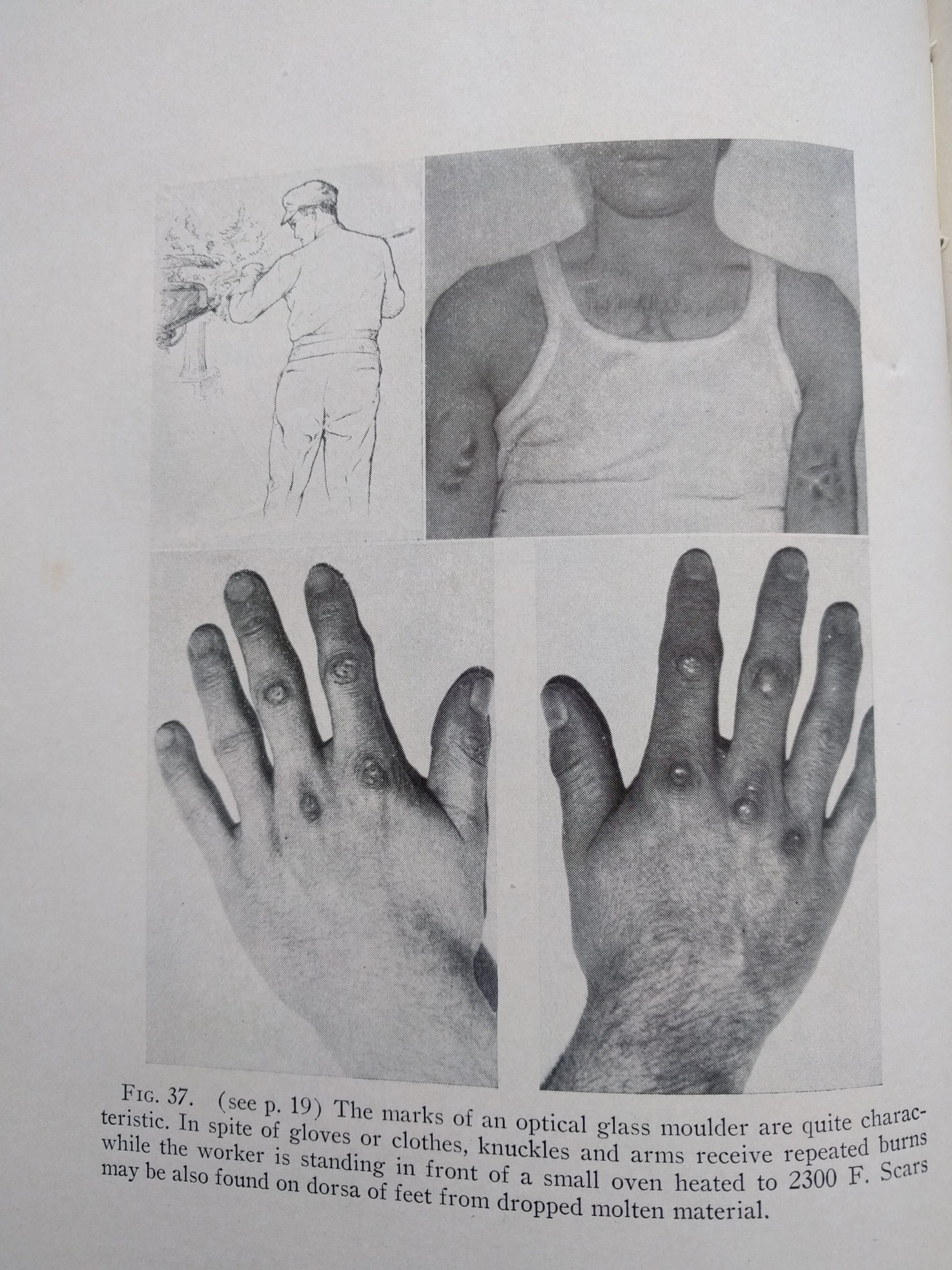

In the introduction and preface, there is an anecdote about a trauma surgeon the author studied under during his internship. Called upon to identify patients who were unconscious or had no identification, the surgeon would carefully inspect the hands for telltale calluses that might indicate what were delightfully termed the "stigmata of occupation." This had far-reaching consequences, even when the patient did not survive, since correctly identifying a body might mean securing a veteran's pension for the surviving spouse.

There are amusing sections highlighting how a careful review of an individual's hands or lips might distinguish between professional tuba, trumpet and trombone players.

To turn the pages is also to see livelihoods from a prior century that no longer exist:

- artificial flower maker

- silverware maker who forces knife blades into silver handles

- spectacle frame polisher

- optical glass molder

- boat caulker

It's enlightening to realize that craftsmanship and a deep mastery of skills once flourished. I am reminded of an oft-repeated quote from Robert Heinlein:

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyse a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

This is the sort of quote that takes me by the lapels and shakes some sense into me - life is short, and there is so much to learn and do beyond the confines of the practice of medicine.

Has a high income and meaningful work hoodwinked us into believing we ought to spend our lives as super-specialized insects?

While a physician's job does not involve manual labor, we carry our own invisible "stigmata of occupation."

Has being a doctor left you with occupational marks you'd rather not have?