Editor's note: My wife likes to quote an old world saying that there's a lid for every pot (usually used in the context of dating).

Similarly, I want every reader of this blog to find at least one interviewee that reflects the reader's peculiar circumstances and compulsions.

This interviewee qualifies, in the best of ways, as both peculiar and compulsive. The Loonie Doctor is a novel variant of a doc who cut back: an academic workaholic who reduced his excessive commitments to a single full-time equivalent.

I've worked with and learned from Loonie Docs throughout my career in medicine, and if they can learn to smell the roses just a bit more, I'll consider this interview a valuable contribution to the canon. Baby steps!

Finally, for the gringo reader, Loonie refers (at least in part) to the informal name for the Canadian one dollar coin.

What is your specialty, and how many years of residency/fellowship did you complete? How old were you when you began to cut back? How many years out after completing training was this?

My clinical specialties are respirology and critical care. I was fortunate to be able to overlap and complete them in six years. (It would now take seven).

I also spent time training in medical education and leadership – although the paths for that were much less recognized back then. They form the back-bone of my academic and administrative roles in a teaching hospital.

I started cutting back gently at age 36 and more meaningfully at age 40. That would be 6 and 10 years into practice respectively.

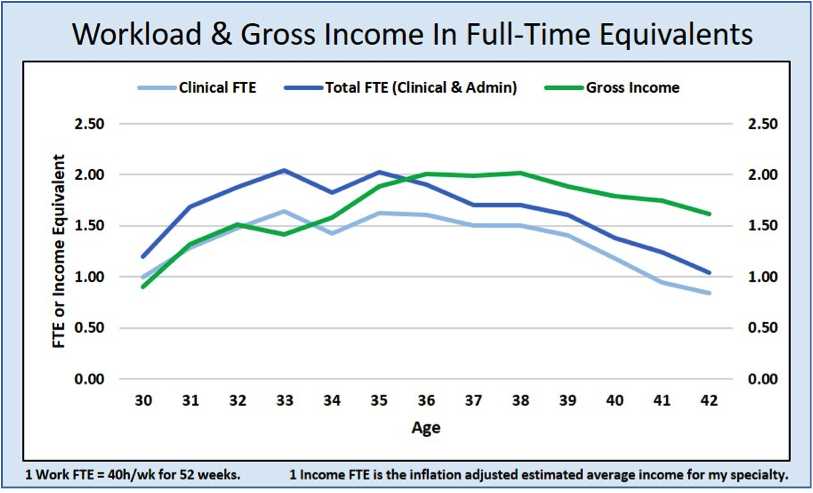

I need to put my imposter syndrome around being “A Doc Who Cut Back” out there right up front. If you count a 40h/wk work-week as one full-time-equivalent (FTE), I worked up to twice that for a long time while building my practice. I have “cut back” to 1 FTE.

That may sound ridiculous to the average person. However, many docs who work in busy or multiple specialties or in academic centers would consider 40h/wk as heavenly.

The other factor not captured in average hours per week is that in ICU, it is bunched up. I will typically work 60h in one week and 0-12h the next. The hours can also be unsociable - I still round in the morning about 22 weekends per year and am in-hospital overnight about four times per month.

So, for me, cutting back is a matter of perspective. I added the above paragraph in because I am writing this (and my wife is editing it) at the end of a busy week on service. She called “BS” on my “cutting back to full-time” claim due to the recency bias. Those who read my blog, will not be surprised that I have actually tracked my work and income while building my practice. It is charted below. Imagine how frustrating being married to me must be 😉

What did your parents do for their livelihood? Would you characterize your upbringing as financially secure or insecure? How did your upbringing affect the money blueprint you inherited - both positive and negative?

My mom was a nurse and my dad was a tech in the lab of a small hospital in an isolated area of northern Canada. They both retired at age 54. My upbringing has definitely affected my financial blueprint.

Growing up where I did had many positives. My parents’ jobs were very secure because few people were willing to move up there for work. We also honestly did not have easy access to many of the luxuries that are at most people’s finger-tips. Impulse shopping was virtually impossible. You could buy common items easily, but a big or boutique purchase meant a 6h round trip or a 6 week wait-time. Keeping up with “Joneses” meant having a simple house (there were no big ones) and a car.

A sports car would leave the undercarriage strewn down the street. So, the luxury vehicle of choice was a nice truck and/or a ski-doo. We had neither. Pretty much everything was within walking distance in town and you’d spend as much time starting and warming your car up as it took to walk most places. Our vehicles just needed to make it for 10 minute long trips to cart groceries etc.

That description may make it sound like we did not have the resources to live comfortably. Nothing could be further from the truth. We were surrounded by forests, lakes, and natural resources. This is where people spent their time or hanging out together huddled in cozy homes.

With all that outdoor space there were also fewer rules needed to keep people from getting into each other’s space. You also weren’t anonymous and needed to depend on each other. Excellent for regulating behavior. Freedom & community. My wife and I currently live near a major city for my career. We spend inordinate amounts of money trying to recapture that freedom and connection with nature via a large country estate and frequent motorhome travel.

My parents had a budget and made very deliberate spending decisions. Part of that was based on the fact you had to wait and plan for purchases. However, a larger part was that their major financial goals were to fund educations for my sister and I and to be able to retire early and head “South”. My aunt and uncle had retired early (age 40) and they wanted to join them.

Together, these themes shaped my financial perspective. Deliberate spending of time or money and clearly articulating priorities are cornerstones to my financial success. My upbringing made that a natural path for me. However, it also left me inexperienced in how to deal with making large amounts of money and having easy access to luxuries. That led to some lessons learned the hard way.

What motivated you to cut back? [Family / burnout / relationship / divorce / lawsuit/ other?]

Multiple factors:

- The biggest one was that I could see my kids rapidly growing up and my wife and I getting older. I mean, just me getting older. You can’t recapture time and I wanted to spend more of it with them in the present.

- Much of the work we had done to build up our practice had come to fruition. The quality of work-life is now excellent and our academic productivity off the charts. We optimized the financial efficiency of our practice. So, I could work a lot less for a little less pay. With that environment, there is now a line-up of people looking to do more of that clinical work.

- After recent fee claw-backs, university tithes on clinical earnings, and hitting our recently increased 54% top marginal tax rate – I only take home 33 cents on the Loonie. I previously could defer some tax by leaving money in my corporation, but the government recently changed the rules to limit that also. They want the money now. The most logical response to little return on effort is to redirect your effort elsewhere.

I would be embracing medical martyrdom for both myself and my family if I continued to work more than needed to meet our needs and have a fulfilling career.

What were the financial implications of cutting back? Did you downsize home or lifestyle? Slow your progress to retirement? Describe your thought process in making these tradeoffs.

We have actually upsized our lifestyle because we travel more and I am spending more money on hobbies.

One key to this has been sequence. We heavily front-loaded our working/saving. That put us in the position to either retire comfortably now or work less and spend/give more.

The second piece was that we paused to look at our situation and deliberately change course. We chose a balance of working at an enjoyable level and living it up more while not working.

How did colleagues react to your decision? How did you respond?

Our department has become pretty cohesive, having been through major changes in evolving our practice together over the past decade. We have actually encouraged each other in cutting back clinical work to pursue academic or personal interests. It was also over-due for me to cut back.

Anytime you build a new service, there is an investment of effort to get it running before it becomes lucrative and everyone wants in. I had done a lot of that. My group was both grateful for that and happy to step in.

Those outside of our group are a bit more fascinated. In my case specifically, there are some assumptions that I will follow “the script”. I rose very rapidly through our hospital chain of command and performed well. My purpose was to lead an overhaul of our workplace, but is usually assumed to be about ambition.

People are often shocked to find out that my next step won’t necessarily be “up”. I will only take on a leadership role where I feel there is something tangible that I can accomplish in it. The best opportunities lay through going where needed. That was as physician leader for the last decade. For the next decade, it is as father and husband. After that, who knows?

Was your family supportive or critical? Partner? Parents? Children?

All very supportive. They have been after me to scale back for years and if anything it hasn’t been fast enough for their liking. The more time I spend at home, the more I am missed when gone.

What have been the main benefits of your decision to cut back?

My time at work is more productive and my time at home is more enjoyable. Both stem from being better physically and mentally rested. Rather than in mere survival-mode.

Main drawbacks?

None.

Did you fear your procedural or clinical skills might decline? How did you address this concern?

I did so much hands-on procedural work early on that I am not worried. I still work clinically about half the weeks of the year which gives plenty of exposure.

If you are honest, how much of your identity resides in being a physician? How did cutting back affect your self-image, and how did you cope?

Most who know me outside of work are surprised that I am a physician. Probably because I wear the most comfortable, least formal clothes that my handlers will let me get away with. And I am a bit of a smartass. I know. Shocking.

However, I am proud to be a physician and of the work that I do. My biggest pride is actually seeing what our physician group is doing and knowing that I helped that in a small way. That will continue regardless of how many hours I personally put in.

If you had not gone into medicine, what alternate career might you have pursued?

I was going to teach high school science.

What activities have begun to fill your time since you cut back?

My kids and I do karate together. Our family also likes “glamping” and biking. I like to take on unusual projects in my workshop or around our property. Blogging is incredibly time consuming. I find these activities stimulating and they are enmeshing myself or our family into communities. Whether that is at our karate club, in our neighborhood, or on the internet.

The other aspect of imposter syndrome I have around “cutting back” is that I am still very busy. I don’t sit around much and my family would still tell you that I am a “workaholic”. The “work” is just different.

If approaching retirement, what activities have you begun to prioritize outside of medicine so that you retire to something?

I don’t plan on “retiring” from medicine until my kids are launched. Maybe not even then. It will depend on where I think the opportunities to have some fun and make some impact lie.

Did you front-load your working and savings, or did you adopt a reduced clinical load early in your career? What was the advantage of the route you chose? What would you do differently if you were graduating residency today?

Definitely front-loaded. I would do it that way again because that allowed me to work hard while physically able and build a practice that I can reap the benefits of for years to come. Building financial independence early gives you more options later. Life doesn’t get less complex.

The potential downside of front-loading is that there is sacrifice in other areas during the early years. If single, you are free to do your thing. Take advantage of that. If you are in a relationship, you need to make sure that your partner is on board and shares your vision.

My wife supported me financially while in training. As my career ramped into overdrive, she picked up the slack in other areas of our lives also. We are a unit and both of our workloads were front-loaded. That can only be done if you openly communicate and course correct frequently as needed. It also can’t be done indefinitely. My only regrets are a few times when I didn’t listen to her enough and focused too much on the destination rather than the journey. Fortunately, she is as persistent as I am.

Some observations stand out about the good doctor's life path and story:

- His parents served as role models for budgeting and planned early retirement.

- A childhood where there were not significant differences in luxury and standard lifestyle may have played a role in not needing to keep up with the Joneses.

- Aging is a great motivator. Watching children age and prepare to fly the nest often motivates even the most stubborn workaholic to cut back.

- A self-image as an outsider (one who might not be perceived as a physician by others who don't know him) seems to exert a protective effect against living a more inflated doctor lifestyle.

- A communicative partner who signs on for a front-loaded career is essential to preserve both career and relationship.

The delightfully irreverent images are courtesy of Loonie Doc. You can find more of this wry, pithy writing style and deeply analytical mind at looniedoctor.ca (not dot com) because, Canada!